The Time is Now to Connect Indigenous-led Environmental Protection with Climate Policy

By Nate Edwards, Natalie Chodoriwsky

Globally, 5.1 billion people lack meaningful access to justice—undermining climate resilience and forest protection. Within this global justice gap, 2.3 billion people lack documentation of housing or land tenure, while 1.1 billion lack legal identity—leaving them vulnerable to land grabs and environmental harm. Exclusion from the protections that the law provides particularly among marginalized groups—including Indigenous peoples—puts them at risk for exploitation and abuse.

Indigenous peoples manage over 25 percent of the world’s lands and steward 80 percent of its biodiversity, including over 25 percent of carbon stored in tropical forests. However, they remain largely excluded from national and global climate decision-making processes and receive less than 1 percent of climate finance to support their efforts. Despite delivering conservation outcomes equal or better than those of governments, Indigenous communities face systemic barriers when trying to protect the environment.

Some of these barriers include inadequate legal protection and a lack of access to legal tools, limited representation in climate governance negotiations that affect them and their lands, and a lack of funding to uphold their rights. The convergence of these factors leads to exploitation and the denial of environmental stewardship.

International frameworks and forums such as the United Nations (UN) Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders, the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, and the Glasgow Climate Pact, seek to better link Indigenous peoples and governance systems, yet they fail to meaningfully connect with local realities. Despite progress in legal recognition, advocates argue that a rights-based approach to national climate action remains largely absent.

People-centered justice (PCJ) offers a pathway to close these gaps by addressing the growing legal needs and structural injustices faced by climate-affected Indigenous and other forest communities. Access to justice and rights-based approaches can increase community resilience, support adaptation, and reduce forest destruction.

There is an urgent need to increase rights-based approaches to support Indigenous and other local environmental stewards. This will require two parallel efforts. First, more support for access to justice for communities on the ground, and second, establishing stronger links between local movements and national and international agenda-setting platforms. These combined efforts will support forest protection and the environmental integrity of Indigenous territories.

Financing Locally-led Justice Initiatives

The first step is to better support grassroots efforts that increase access to justice and close the justice gap. Legal empowerment, where Indigenous and marginalized forest communities know, use and shape the law to assert rights, contest unjust power relations, and demand accountability, is a powerful tool that facilitates these objectives. By shifting power to those most affected, this approach enhances both the agency and capacity of these communities. Resourcing locally-led grassroot groups with funding, knowledge, and networks is the most sustainable approach to advance land and tenure rights, hold duty-bearers accountable, and protect forest ecosystems.

In the Philippines, the Nuclear and Coal-Free Bataan Movement educates communities about their environmental rights and is building a grassroots movement to protect against damages from the fossil fuel industry. This initiative exemplifies how knowing the law empowers people to assert their environmental rights.

Meanwhile in Mongolia, Steps Without Borders is actively using the law to challenge climate injustice in the courts. They have successfully overturned two fraudulent environmental impact assessments, demonstrating the impact of using legal avenues to address and rectify environmental wrongs.

In Ghana, Wacam has successfully challenged regulations allowing mining in forest reserves, notably protecting Kakum National Park from exploitative activities. Through their advocacy for policy change (shaping the law), Wacam has not only preserved the ecological integrity of the area but also safeguards the rights and livelihoods of local communities against the adverse effects of environmental degradation.

Similarly in Brazil, where indigenous rights are constitutionally recognized, Instituto Preservar has effectively used legal empowerment strategies like climate litigation and grassroots legal education to halt the construction of the Nova Seival coal-fired power plant in Rio Grande do Sul, protecting local ecosystems and the rights of rural and Indigenous communities from the harmful impacts of extractive industries (using the law).

Such examples highlight the pivotal role of grassroots legal action in driving significant environmental victories and advancing land rights in the Global Majority. They demonstrate the power of supporting locally-led environmental justice initiatives to create networked impact. However, creating a systemic shift requires connecting networked impact with agenda-setting platforms.

Linking Local Leaders with National, Regional, and Global Platforms

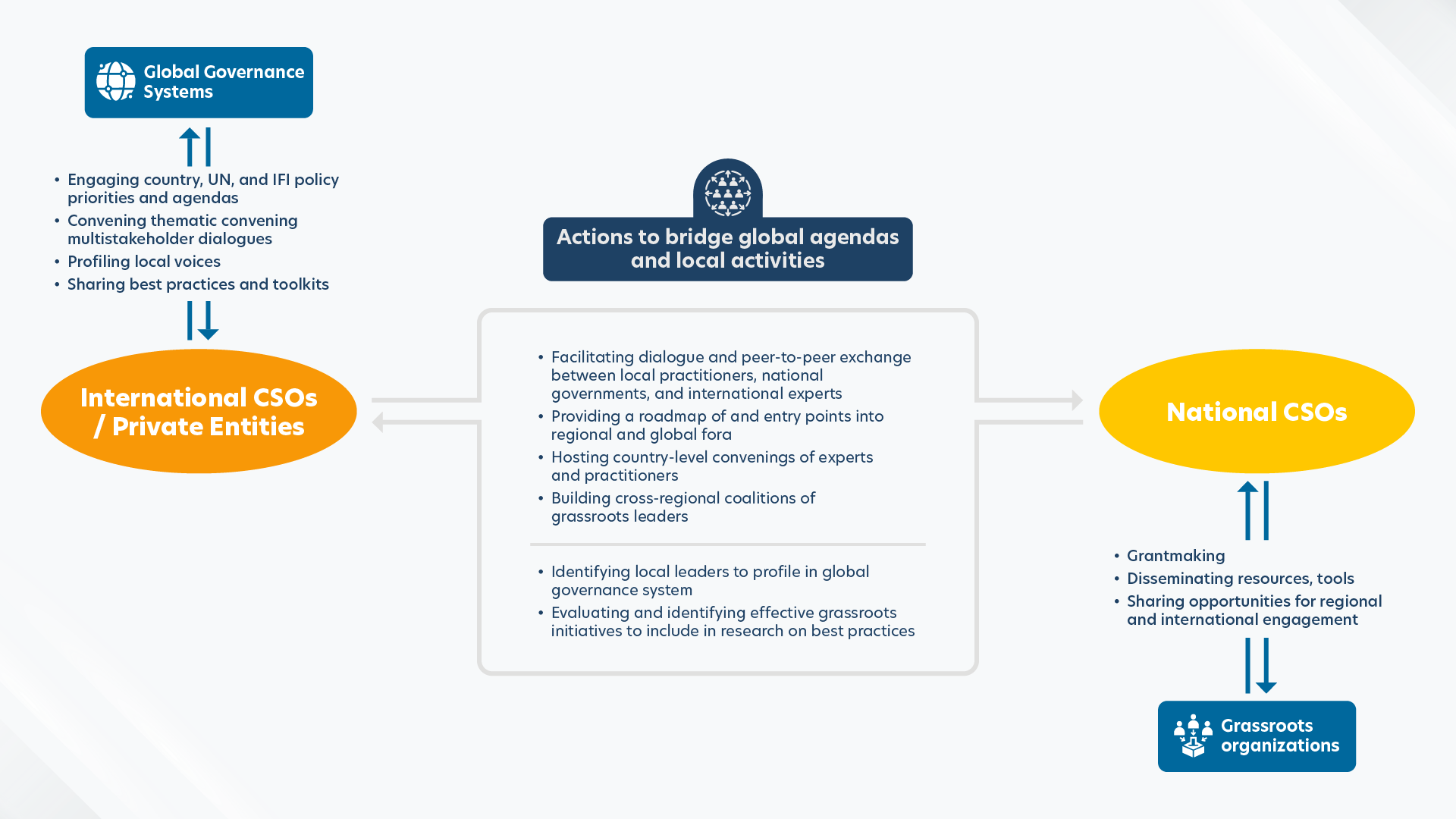

While it is imperative to better support local efforts, it is equally important to strengthen links between local activities and both national and international processes. Connecting local action to global platforms is essential to shifting power to those most vulnerable, therefore ensuring forests are protected through indigenous-led environmental governance.

At the national level, convenings and peer-to-peer exchange of best practices between local leaders and national stakeholders can help to strengthen connections between Indigenous or community-led initiatives and national policy and finance agendas, and therefore, increase opportunities for local leaders to positively influence those agendas.

But it is not enough to provide access to decision-making platforms without the accompanying capacity to affect change within them. Thus, facilitated exchanges at the national level can be paired with the mapping of entry points into decision-making platforms and training on how to access regional and global agenda setting platforms. This can support opportunities to inform and influence discussions on jurisdictional financing and normative frameworks.

At the international level, systemic change could be driven through coalition movements to strengthen access to justice, uphold rights, and improve livelihoods for Indigenous and other local environmental defenders. Civil society organizations can support bilateral engagement for local actors with permanent missions to the UN in New York and Geneva, UN agencies, and international financial institutions. This helps to set priorities to support the rights of Indigenous and other environmental defenders through access to justice. In parallel, multi-stakeholder closed door discussions, and public dialogues on specific thematic areas can socialize best practices during key climate moments like the UN General Assembly Main Committee meetings, the Conference of Parties (COP), the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, UN Ocean Conference, and the Human Rights Council.

Finally, fully institutionalizing this movement requires a database of evidence on locally-led success stories. A key element of shifting power to local leaders is to amplify the successful impact of Indigenous and local communities working on access to justice within the international policymaking community. This is done through published research on successful practices and published interviews with the local leaders working on the ground.

Ultimately, multilateral institutions, in tandem with governments, civil society and private organizations, have to commit to increasing opportunities to exchange ideas between local, national, and international actors working on rights-based approaches to environmental protection. Expanding access to decision-making spaces, and promoting opportunities for peer exchange, will amplify rights-based approaches to environmental governance.

Conclusion

Resourcing Indigenous and community-led groups to advance land and tenure rights, hold duty-bearers accountable, and protect the environment supports people-centered, rights-based, and sustainable climate justice strategies. By pairing local support with coordinated national and global engagement, those with lived experience can better access, and influence, agenda-setting platforms, participate meaningfully in governance processes, and safeguard their territories from environmental harm. Taken together, this approach could support inclusive people-centered climate justice frameworks that secure rights, enhance livelihoods, and ensure the full participation of Indigenous Peoples in climate governance systems. If done effectively, this could be a gamechanger contributing to systemic shifts in climate policy around the world.

Related Resources