Climate Change, Injustice, and Displacement: Unraveling the Nexus

By Stacey Cram, Non-Resident Fellow, Pathfinders for Peaceful, Just and Inclusive Societies, NYU Center on International Cooperation (CIC)

As the world grapples with the escalating climate crisis, a critical dimension remains overlooked: the profound relationship between climate change, access to justice, and displacement.

For billions of individuals already grappling with justice problems, the impacts of climate change exacerbate the challenges they face, with the most vulnerable disproportionately suffering from the resulting consequences—including forced displacement from their homes and homelands.

Without decisive action, climate change will widen the global justice gap, creating new forms of injustice that will stall progress towards poverty alleviation and sustainable development and drive more people to leave their homes. Beyond the trauma of being forced to relocate within a country or across borders, many are exposed to additional justice challenges related to property rights, resettlement, access to services, labor and other social protections, and social belonging. This often results in a devastating “second exile” that keeps millions of people in a perpetual limbo, unable to rebuild their lives even long after the original climate disaster that uprooted them has ended.

Understanding the climate-justice-displacement nexus is crucial to design solutions that support those most impacted by climate change. When used proactively, people-centered justice tools can mitigate climate injustice and its links to displacement and ensure pathways for safe movement, settlement, and return.

The Disparate Impacts of the Climate Crisis: A Conduit of Injustice that Drives Displacement

Climate-induced displacement can result from disasters like cyclones or floods, creating immediate humanitarian and justice needs that lead to temporary displacement if suitable support is made available quickly or a more protracted exile if such support is withheld. Slow-onset climate dynamics can also trigger more permanent movements over a longer time. Displacement can occur as a result of exploitation, such as traffickers leveraging the dissatisfaction of vulnerable climate populations. At other times, forced evictions compel populations to relocate under dire conditions. In Tanzania, 70,000 mostly indigenous residents have been evicted by their government from the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, with observers saying the process has fallen far below internationally recognized standards of free, prior, and informed consent. Even well-intended efforts to support adaptation or just transitions can exacerbate challenges by failing to use a people-centered approach. Renewable energy projects across the globe are replicating development-induced displacement trends, leading to mass evictions and conflicts over land rights.

Meanwhile, traditional climate justice arguments often center on reparations and state-to-state inequities. While important, these conversations frequently miss the disparate impacts of climate change communities face. For example, extreme weather events have disrupted the livelihoods of five million people in the Sundarbans region of India, a population that is among South Asia’s poorest and most vulnerable, forcing many to rely on uncertain incomes and increasing justice challenges related to labor and debt. Wildfires in the United States have put millions of homes at risk. Yet, insurance companies are scaling back coverage, leaving many, especially poorer households, unable to repair their homes and facing long-term financial damage without viable grievance mechanisms. In Chile’s Sacrifice Zones, residents suffer from pollution-related diseases and increased mortality rates. However, regulatory oversight often falls short for these communities, and access to justice remains elusive. These disparate impacts are instead left to fester, creating a key conduit of injustice that can and frequently does culminate in internal or cross-border displacement.

Indeed, the IPCC has found that climate and weather extremes increasingly drive every kind of environmental (im)mobility, including displacement, migration, and planned relocation. Ultimately, for many people, uprooting themselves is a more viable option than remaining in unjust and vulnerable situations. At present, most movement is internal rather than cross-border.

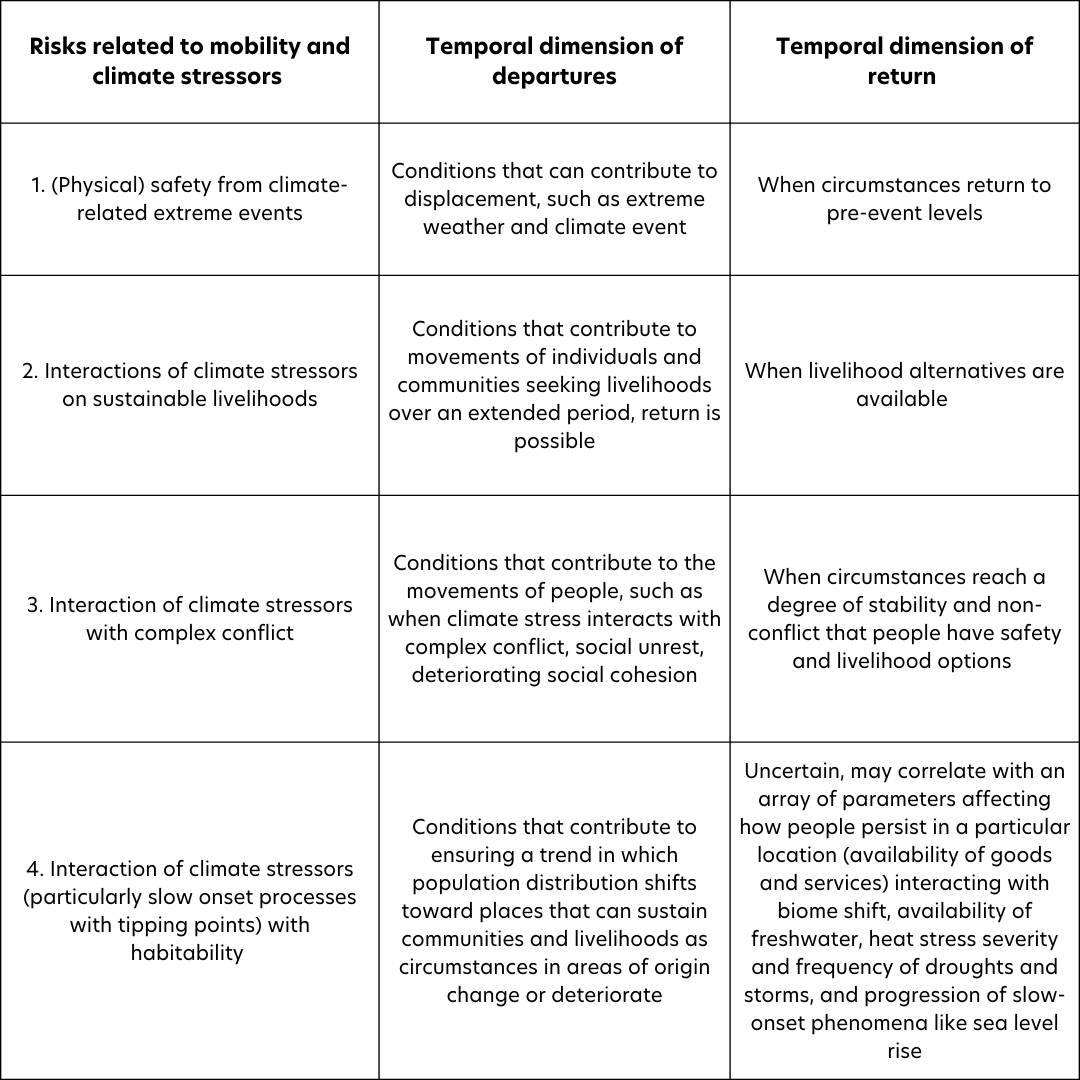

Risks and temporal dimensions of human mobility in the context of climate change

Source: Koko Werner

The fact that the climate crisis is and will be a major exacerbator of multi-causal displacement is increasingly beyond dispute. Having mixed motives for movement makes it especially hard for people to fit into pre-existing categories of “refugee” or “migrant.” When questioned, many individuals cite climate change as a secondary factor that prompted their move. This may be because people focus on challenges such as lost livelihoods or increased conflict and do not attribute these challenges to climate. It may also be because existing global protection frameworks do not adequately account for climate-induced displacement, so those needing protection focus on other factors, such as violence, that may qualify them for refugee protection. This failure to identify climate injustice as a driver for forced migration, and one that merits protection, can fuel a negative narrative of economic migrants and “bogus refugees” and overlook the role that justice actors could play in addressing climate injustice and reducing forced migration from a people-centered perspective.

Understanding climate justice challenges is essential for resilience and adaptation strategies to meet growing legal needs and structural injustices within communities and for populations on the move. Existing international legal frameworks for displaced people are not designed to address multi-causal cross-border displacement, and the profound lack of legal pathways and protections can fuel additional justice challenges, including forcing displaced people into dangerous travel routes while on the move and into an exploitative informal sector where they are vulnerable to abusive labor, debt, and housing practices in the places they seek, but too often do not find, refuge.

People-Centered Justice and Climate Displacement

With overlapping ambitions to uphold rights, improve resilience and adaptation, support livelihoods, and ensure access to services for people on the ground, cross-sector collaboration between humanitarian and justice actors within the climate-justice-displacement nexus is ripe for action. Already, practical people-centered solutions are emerging worldwide, successfully resolving justice challenges for climate-impacted communities, curbing displacement, and supporting people to move safely.

Effective strategies include locally led adaptation efforts that prevent property destruction and livelihood loss, legal empowerment and community organizing, strategic litigation, global advocacy, and planned relocations. For example, community paralegals in Sierra Leone and Nigeria have mobilized residents to secure better land lease terms with a Chinese rubber firm that seized land, and halt evictions from informal settlements through legal action and dialogue with authorities. In Fiji, at-risk communities have worked alongside government and scientific experts to proactively design planned relocation efforts before a climate disaster forces them to move, ensuring vulnerabilities associated with displacement are mitigated and that just solutions are in place.

Moreover, the IPCC has recognized strategic litigation as pivotal in shaping climate policy. Positive results include New York City residents winning a $1.1 million settlement for pollution from the North River Wastewater Treatment Plant and the KlimaSeniorinnen group successfully arguing that Switzerland’s climate policies violated their human rights. As the volume of climate litigation grows, it establishes a robust legal precedent, with 55 percent of cases resulting in climate-positive rulings that directly influence new policies.

In the absence of global frameworks, some Governments are proactively protecting climate-displaced populations’ rights. Peru’s Climate Change Framework Law addresses forced migration caused by climate, while Colombia prepares to legally recognize climate-displaced people, granting priority access to essential services. Sierra Leone’s Customary Land Rights and National Land Commission laws grant communities the right to Free Prior Informed Consent over industrial projects, and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights advisory opinion on human rights and the climate emergency will soon guide countries in the region with open proceedings ensuring communities are heard from directly.

Recommendations

Moving forward, justice and humanitarian actors should capitalize on opportunities to collaborate on anticipatory action, leveraging early warning systems and integrating political economy analysis with weather event prediction to identify, empower, and safeguard at-risk populations. Establishing holistic, accessible, and affordable justice services can help climate-impacted communities resolve various justice needs and reduce the likelihood of displacement, even while we wait for institutional frameworks to adapt to new forms of mobility.

To this end, governments should include climate risks, justice challenges, and migration considerations in national policies, bolstering urban planning and development plans, relocation frameworks, and humanitarian pathways for internally displaced and refugee populations. The Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement offer a framework for addressing justice challenges in climate-impacted contexts that uphold the rights and dignity of displaced persons.

Furthermore, significant data gaps must be filled, including the justice challenges people face in climate-impacted contexts, how those fuel environmental mobility, and what new justice challenges displacement causes on the other side of migration corridors.

The voices and experiences of those directly impacted by climate change must be at the forefront of developing these solutions, and the most at-risk populations must be prioritized, aligning with the 2030 Agenda’s commitment to leave no one behind.

The climate-justice-displacement nexus offers a new perspective on the relationship between climate change and justice, recognizing the chain reaction that climate change has on people’s justice problems and how these, in turn, fuel further marginalization and environmentally induced displacement. A forthcoming paper will examine how these interconnected challenges require collaboration between humanitarian and justice actors, proactive and people-centered strategies, and inclusive policy frameworks. By working together to prioritize justice for all, we can break the cycle of climate injustice and prevent, address, and resolve climate-induced displacement.

This blog is a publication of the Justice for Displaced Populations (J4DP) initiative, founded at the New York University Center on International Cooperation (CIC) in 2022 as a partnership between the Pathfinders for Justice and Humanitarian Crises programs. In 2024, a partnership was formed between Pathfinders for Justice at CIC and The New School’s Zolberg Institute on Migration and Mobility to continue this work.

Related Resources